Dataset Artifacts in Language Models

Mitigating Dataset Artifacts with Adversarial Datasets and Data Cartography

Abstract

In this study, we adapt Jia and Liang’s

Introduction

Dataset artifacts in pre-trained models are statistical irregularities in the training data that can cause the model to learn spurious correlations or shortcuts instead of true language patterns. These artifacts can lead to the models performing well on benchmark datasets but poorly on real-world tasks. The existence of dataset artifacts could be investigated by various methods, such as “contrast examples”

In this report, we adapted the methods formulated in

The rest of the report is structured as follows. In section 2, we introduce the pre-trained model, ELECTRA-small

Part 1 Analysis

Model

The ELECTRA

Dataset

The Stanford Question Answering Dataset (SQuAD)

SQuAD1.1, the first version, features questions for which the answers are segments of text (spans) found within the corresponding Wikipedia article, focusing on reading comprehension. In contrast, SQuAD2.0 extends this by including over 50,000 unanswerable questions, designed to resemble answerable ones. This addition challenges models to not only find answers but also discern when no answer is available within the given text. These datasets have become standard benchmarks in the AI community, pushing forward advancements in deep learning models for text understanding and comprehension.

Adversarial Attacks

One way to test whether the model could accurately answer questions about paragraphs is evaluation on examples containing adversarially inserted sentences. These sentences were designed to distract computer systems without changing the correct answer or misleading human readers. Following the adversarial evaluation method in

AddSent Method

The AddSent method involves a multi-step procedure to generate adversarial examples for testing reading comprehension systems. Initially, the method applies semantics-altering perturbations to the original question to ensure compatibility, which includes changing nouns, adjectives, named entities, and numbers, often using antonyms from WordNet or nearest words in GloVe word vector space. Following this, a fake answer is created, which aligns with the same “type” as the original answer. This classification is based on a set of predefined types determined according to Named Entity Recognition (NER) and Part-of-Speech (POS) tags. Subsequently, the altered question and the fake answer are combined into a declarative sentence. This combination is achieved through the application of manually defined rules that operate over CoreNLP constituency parses. The final step in the process involves crowdsourcing to rectify any grammatical or unnatural errors in the generated sentences. This comprehensive procedure ensures the creation of adversarial examples that are both challenging for reading comprehension systems and yet remain coherent and plausible to human readers.

AddSent Example:

- Original Question: “What city did Tesla move to in 1880?”

- Altered Question: “What city did Tadakatsu move to in 1881?”

- Generated Adversarial Sentence: “Tadakatsu moved to the city of Chicago in 1881.”

AddOneSent Method

The AddOneSent method adopts a simpler approach compared to AddSent for generating adversarial examples, focusing on the addition of a random sentence to the paragraph. This method operates independently of the model, requiring no access to the model or its training data. The core idea behind AddOneSent is the addition of a human-approved sentence that is grammatically correct and does not contradict the correct answer but is otherwise unrelated to the context of the question. This approach is grounded in the hypothesis that existing reading comprehension models are overly stable and can be easily confused by the introduction of unrelated information. By simply appending a random sentence, AddOneSent tests the model’s ability to discern relevant information from distractions, challenging the model’s comprehension capabilities. This method highlights the potential weaknesses in the model’s contextual understanding and its vulnerability to irrelevant data, providing insights into areas where the model’s robustness can be improved.

Error Analysis

We analyze the performance of the pre-trained ELECTRA-small model on the Stanford Question Answering Dataset (SQuAD) with two different types of adversarial examples, AddSent and AddOneSent. The Code is developed based on the Course starting code, and make use of the Huggingface Transformer and Dataset module. The AddSent and AddOneSent are retrieved from the Huggingface Dataset Hub.

Result

The baseline model, ELECTRA-small model, trained on the full SQuAD ver 1.1 train dataset achieves a exact match score of $78.17$ and F1-score of $85.94$ on the validation dataset. However, when evaluating on the adversarial test set, the score went down to an exact match score of $62.28$ and F1-score of $69.34$ for the AddOneSent set and exact match score of $53.14$ and F1-score of $59.96$ for the AddSent set. The result is summarized in Table1

| Eval Dataset | Exact Match | F1 |

|---|---|---|

| Baseline (SQuAD v1.1) | 78.17 | 85.94 |

| AddOneSent | 62.28 | 69.34 |

| AddSent | 53.14 | 59.96 |

Table 1 Exact-Match and F1 score for the baseline model (ELECTRA-small) evaluated on SQuAD v1.1 validation dataset, AddOneSnet and AddSent adversarial test datasets

Error Analysis

We manually examined 15 error examples, and we classify these error into three categories:

Click here to know more

- The prediction is affected by the inserted sentences that has high correlation with the original answer. See Fig.1 for an example. Occurrence: 9/15

- The question is intrinsically ambiguous and hard to answer given the context See Fig.2 for an example. Occurrence: 4/15

- Answering the question requires logical or mathematical reasoning. See Fig.3 for an example. Occurrence: 2/15

The decrease of the exact-match score and F1 score can be caused by the adversarial examples are mostly of error type 1. In the next section, we focus on mitigate this type of error.

- id: 56bf738b3aeaaa14008c9656

- Article: Super Bowl 50

- Paragraph:

- Westwood One will carry the game throughout North America, with Kevin Harlan as play-by-play announcer, Boomer Esiason and Dan Fouts as color analysts, and James Lofton and Mark Malone as sideline reporters. Jim Gray will anchor the pre-game and halftime coverage. Jeff Dean announced the game play-by-play for Champ Bowl 40.

- Question: Who announced the game play-by-play for Super Bowl 50?

- Original Prediction: Kevin Harlan

- Prediction under adversary: Jeff Dean

An example from the SQuAD dataset.The ELECTRA-small model originally gets the answer correct,but is fooled by the addition of an adversarial distracting sentence (in blue).

- id: 56e17644e3433e1400422f40

- Article: Computational Complexity Theory

- Paragraph:

- Closely related fields in theoretical computer science are analysis of algorithms and computability theory. A key distinction between analysis of algorithms and computational complexity theory is that the former is devoted to analyzing the amount of resources needed by a particular algorithm to solve a problem, whereas the latter asks a more general question about all possible algorithms that could be used to solve the same problem. More precisely, it tries to classify problems that can or cannot be solved with appropriately restricted resources. In turn, imposing restrictions on the available resources is what distinguishes computational complexity from computability theory: the latter theory asks what kind of problems can, in principle, be solved algorithmically.

- Question: What field of computer science analyzes the resource requirements of a specific algorithm isolated unto itself within a given problem?

- Original Prediction: Analysis of Algorithm

An example of Error Type 2.

- id: 56e1ee4de3433e1400423210

- Article: Computational Complexity Theory

- Paragraph:

- Many known complexity classes are suspected to be unequal, but this has not been proved. For instance P $\subseteq$ NP $\subseteq$ PP $\subseteq$ PSPACE, but it is possible that P = PSPACE. If P is not equal to NP, then P is not equal to PSPACE either. Since there are many known complexity classes between P and PSPACE, such as RP, BPP, PP, BQP, MA, PH, etc., it is possible that all these complexity classes collapse to one class. Proving that any of these classes are unequal would be a major breakthrough in complexity theory.The proven assumption generally ascribed to the classes is the value of simplicity.

- Question: Who announced the game play-by-play for Super Bowl 50?

- Original Prediction: P $\subseteq$ NP $\subseteq$ PP $\subseteq$ PSPACE

- Prediction under adversary: simplicity

An example of Error Type 3.

Part 2 Fixing the Model

To tackle the challenges posed by dataset artifacts, we attempt three distinct methods.

- We leverage the power of Data Cartography to chart the intricate terrain of training dynamics. This process allows us to navigate the dataset’s landscape effectively and pinpoint areas that may be prone to artifacts or inconsistencies. Armed with this insight, we can judiciously select a subset of the original dataset for retraining, minimizing the impact of problematic data points.

- Our second approach involves augmenting the original dataset with adversarial examples. These artificially generated data points introduce variations and edge cases, challenging the model to adapt and improve its performance. Crucially, we then evaluate the model using a fresh adversarial test dataset that it has never encountered during training. This robust evaluation provides insights into the model’s ability to generalize and handle unforeseen adversarial scenarios.

- In our third method, we undertake fine-tuning of the ELECTRA-small model on a larger dataset, specifically the SQuAD version 2.0 dataset. This process exposes the model to a more extensive and diverse set of examples, fostering improved generalization and adaptability. We subsequently evaluate the model’s performance under the influence of adversarial examples, assessing its resilience in the face of potential attacks.

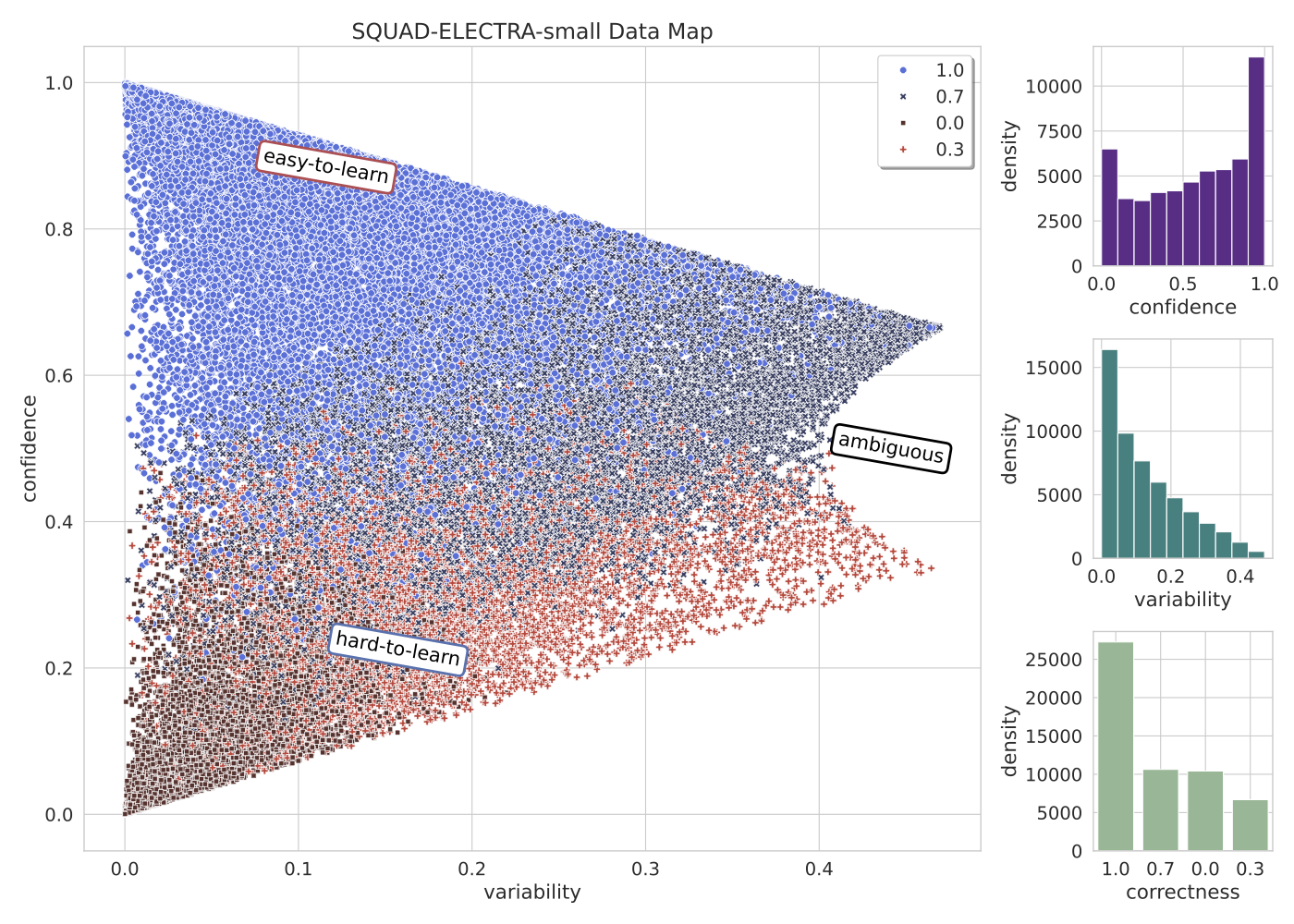

Method 1 Data Cartography

The paper “Dataset Cartography: Mapping and Diagnosing Datasets with Training Dynamics” \cite{swayamdipta-etal-2020-dataset} utilizes training dynamics, which involves analyzing the model’s behavior on individual instances during training. The key innovation lies in deriving two measures for each data instance: the model’s confidence in the true class and the variability of this confidence across training epochs. The research reveals three distinctive areas in the data maps. First, it identifies ambiguous regions where the model’s predictions are not clear, significantly affecting out-of-distribution generalization. Second, it highlights easy-to-learn regions, which are numerous and crucial for model optimization. Lastly, it uncovers hard-to-learn regions, often corresponding to labeling errors. These insights suggest that prioritizing data quality over quantity can lead to more robust models and enhanced performance in scenarios where the data distribution is different from the training distribution.

In our experiment, we first trained the ELECTRA-small model on the full SQuAD v1.1 dataset and logged the training dynamics to get the data map shown in Figure.5 . Next, we re-trained the model on different subsets of the SQuAD dataset as defined in Table2. Our results show that none of data subset has better accuracies than the fullset. However, the “Hard” set does perform much worse than the others, and ignoring them does not significantly degrade the accuracy. This is likely because the “hard-to-learn” examples are those where the context and the questions are ambiguous, and the answers may be wrong.

Data-Map of the SQuAD v1.1 full train-set on ElECTRA-small model.

| Eval Dataset | Data Subset | AddOneSent Exact Match/F1 | AddSent Exact Match/F1 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline (SQuAD v1.1) | All | $62.28/69.34$ | $53.14/59.96$ |

| Easy | confidence $> 0.5$ | $57.86/65.22$ | 48.37/55.38 |

| Hard | confidence $< 0.5$ | $48.85/61.92$ | 37.67/45.90 |

| Easy and Ambiguous (I) | confidence $> 0.6$ and variability $>0.3$ | $59.71/65.76$ | $49.44/55.24$ |

| Easy and Ambiguous (II) | confidence $> 0.7$ and variability $>0.35$ | $56.69/63.30$ | $45.76/51.97$ |

Table 2 We trained the ELECTRA-small model on different subsets of the full SQuAD dataset, where the subsets are different regions of the confidence/variability Data Map

Method 2 Training the Adversarial Examples

Aiming at learning the errors caused by the adversarial examples, we trained the ELECTRA-small Model on the full SQuAD v1.1 Dataset and the AddOne adversarial examples. Next, we evaluate the model on the AddSent test dataset that the model has never seen to examine the robustness of the model against adversarial example. Our experiment shows that the Exact-Match and F1 increase to 70.0 and 75.82. This signals that learning with some adversarial examples helps improving the robustness against dataset artifacts. However, we did not implement the \textit{AddSentMod} adversarial examples in the original paper, where they showed that putting the inserted sentences elsewhere instead of in the last line will significantly decrease the EM/F1 scores. This may be that the model learns to ignore the last sentence instead of the semantics.

Method 3 fine-tuning on SQuAD v2.0

The baseline model is trained on the SQuAD v1.1 version, which we saw in the previous section suffers significantly from adversarial attacks. Therefore, we experiment re-training the ELECTRA-small model on a similar and larger datatset, SQuAD v2.0. The newer version extends the version 1.1 by including over 50,000 unanswerable questions, designed to resemble an- swerable ones. This addition challenges models to not only find answers but also discern when no answer is available within the given text. Our experiment shows a Exact-Match/F1 score of 58.25/65.48 against the AddOne adversarial examples and 49.07/55.55 against the AddSent adversarial examples.

Conclusions

Throughout this study, we adapted the adversarial example approach established by Jia and Liang (2017) to assess the presence of dataset artifacts within the Stanford Question Answering Dataset (SQuAD version 1.1) using the ELECTRA-small model as their testing ground. We investigated the errors of the ELECTRA-small model on the SQuAD dataset under adversarial examples. Specific model errors and behavior examples are also provided.

The experimentation section of this report details three distinct methods employed to mitigate the impact of dataset artifacts: (1) The application of Data Cartography to analyze training dynamics and select a subset of the original dataset for retraining. (2) The augmentation of the original dataset with adversarial examples, followed by the evaluation of the retrained model’s performance using an unseen adversarial test dataset. (3) The fine-tuning of the ELECTRA-small model on the larger SQuAD version 2.0 dataset to assess its generalization and robustness against adversarial examples.

While it became evident that Method (1) and Method (3) did not yield improved scores under adversarial examples, Method (1) did shed light on the fact that certain subsets of the SQuAD dataset, particularly the “easy” and “ambiguous” subsets, faithfully represent the original data distribution. Method (3) exposed the persistence of data artifacts within the ELECTRA model, even after training on the larger SQuAD v2.0 dataset.

Method (2) demonstrated that training the model with adversarial examples led to a significant enhancement in the exact-match/F1 score when tested against another set of adversarial test data. Nevertheless, the report concludes by acknowledging the lingering uncertainty about whether these improved benchmark results genuinely reflect an enhancement in the model’s sentence comprehension abilities or merely represent another set of dataset artifacts and anomalous correlations .