Kmeans Clustering Algorithm with CUDA

Kmeans Clustering Algorithm with CUDA and CUDA Thrust API

Introduction

K-means

In the general framework of the k-means algorithm, we are given a dataset $\mathbf{X} = (\mathbf{x_1}, \mathbf{x_2}, \dots, \mathbf{x_n})$, where each $\mathbf{x_i}$ represents a $d$-dimensional point in a vector space. The goal is to partition this dataset into $k$ distinct clusters $\mathbf{S} = {\mathbf{S_1}, \mathbf{S_2}, \dots, \mathbf{S_k}}$ such that points within each cluster are more similar to each other than to those in different clusters. This is achieved by solving the following optimization problem

\(\underset{\mathbf{S}}{\text{arg min}} \sum_{i=1}^k \sum_{\mathbf{x} \in \mathbf{S_i}} ||\mathbf{x} - \mathbf{\mu_i}||^2,\) where $\mathbf{\mu_i}$ denotes the centroid of cluster $\mathbf{S_i}$.

K-means Algorithm Overview

The standard K-means algorithm follows these steps:

- Initialization: Randomly select K points as initial cluster centroids.

- Assignment: Assign each data point to the nearest centroid based on Euclidean distance.

- Update: Recalculate the centroids of each cluster by computing the mean of all points assigned to that cluster.

- Iteration: Repeat steps 2 and 3 until convergence or a maximum number of iterations is reached.

CUDA Implementation

Basic CUDA implementation

Our CUDA implementation of Kmeans algorithm follows from the the paradigm from the previous section. In the second step, “Assignment” part, we could leverage the thousands of CUDA cores to calculate the nearest center for each point simultaneously. The kernel function is outline below:

__global__ void

mapPointsToCenters(

point *d_Points,

point *d_Centers,

int *d_Labels,

int numPoints,

int numCenters)

{

int idx = blockIdx.x*blockDim.x+threadIdx.x;

if(idx >= numPoints) return;

float min_dist = FLT_MAX;

int min_idx = 0;

for(int i=0; i<numCenters;i++) {

float dist = distance(d_Points[idx], d_Centers[i]);

if(dist < min_dist) {

min_idx = i;

min_dist = dist;

}

}

d_Labels[idx] = min_idx;

}Next, we reset the centroids to zero in preparation for recalculating them in the following step. Each point is then assigned to its nearest centroid. Afterward, we implement a kernel to sum all points sharing the same label and record the number of points assigned to each label in the variable d_ClusterCounts. Finally, we divide the cumulative sum of vectors for each label by d_ClusterCounts to compute the new centroids.

__global__ void

accumulateCenters(

point *d_Points,

point *d_Centers,

int *d_ClusterCounts,

int *d_Labels,

int numPoints,

int numCenters)

{

int idx = blockIdx.x*blockDim.x+threadIdx.x;

if(idx >= numPoints) return;

int clusterid = d_Labels[idx];

int dim = d_Points[0].size;

for(int i=0;i<dim;i++)

atomicAdd(&d_Centers[clusterid].entries[i], d_Points[idx].entries[i]);

atomicAdd(&d_ClusterCounts[clusterid], 1);

}

__global__ void

updateCenters(

point *d_Centers,

int *d_ClusterCounts,

int numCenters)

{

int idx = blockIdx.x*blockDim.x+threadIdx.x;

if(idx >= numCenters) return;

d_Centers[idx] /= d_ClusterCounts[idx];

}CUDA shared memory

In the previous basic CUDA implementation, all the variables are stored and accessed from GPU’s global memory. We could improve our implementation by using GPU’s shared memory. CUDA’s shared memory is a special type of on-chip memory that allows threads within the same block to share data and communicate efficiently. It is much faster than global memory (which resides off-chip) but is limited in size (typically around 48 KB per block). Shared memory is accessible to all threads within a block, and it provides a mechanism for threads to collaborate by reading and writing to a common memory space, enabling data reuse and reducing the need for costly global memory access.

In the second step, where we map each point to its nearest centroid, we could leverage the shared memory and stored the coordinate of the centroids in the shared memory so that it could be accessed much faster. Below is my implementation:

__global__ void mapPointsToCenters_shmem(

int DIM,

double* d_Points,

double* d_Centers,

int *d_Labels,

int numPoints,

int numCenters)

{

const int shmemSize = DIM * numCenters;

//----------LOAD CENTROIDS TO SHARED MEMORY ----------------------------

extern __shared__ double d_Centers_shmem[];

int idx = blockIdx.x * blockDim.x + threadIdx.x;

if (idx >= numPoints) return;

// Load centers into shared memory for each block

for (int i = threadIdx.x; i < shmemSize; i += blockDim.x) {

d_Centers_shmem[i] = d_Centers[i]; // Copy from global memory to shared memory

}

//----------LOAD CENTROIDS TO SHARED MEMORY ----------------------------

__syncthreads(); // Ensure all centers are loaded before proceeding

// Find nearest center

double min_dist = DBL_MAX;

int min_idx = 0;

for (int i = 0; i < numCenters; i++) {

double dist = 0.0;

for (int j = 0; j < DIM; j++) {

double diff = d_Points[idx * DIM + j] - d_Centers_shmem[i * DIM + j];

dist += diff * diff;

}

dist = sqrt(dist);

if (dist < min_dist) {

min_dist = dist;

min_idx = i;

}

}

d_Labels[idx] = min_idx;

}CUDA Thrust

The CUDA Thrust library is a high-level, C++-based parallel programming library designed to simplify GPU programming using NVIDIA’s CUDA architecture. It provides a set of STL (Standard Template Library)-like data structures and algorithms optimized for parallel execution on CUDA-enabled devices. Thrust abstracts the complexities of CUDA, allowing developers to write efficient parallel code with minimal knowledge of low-level CUDA programming. Below we highlight the key points.

Calculate distance between d-dimensional vectors

Given two d-dimension vectors, we could use the Thrust API to calcualte their euclidean distance as:

double distance(const thrust::device_vector<double>& centers,

const thrust::device_vector<double>& old_centers,

int DIM,

int numCenters,

thrust::device_vector<int>& d_center_idx,

thrust::device_vector<double> &squared_diffs)

{

thrust::device_vector<double> squared_diff_centers(numCenters);

thrust::transform(thrust::device,

centers.begin(), centers.end(),

old_centers.begin(),

squared_diffs.begin(),

thrust::minus<double>()

);

thrust::transform(thrust::device,

squared_diffs.begin(), squared_diffs.end(),

squared_diffs.begin(),

thrust::square<double>()

);

thrust::reduce_by_key(

d_center_idx.begin(), d_center_idx.end(),

squared_diffs.begin(),

thrust::make_discard_iterator(),

squared_diff_centers.begin(),

thrust::equal_to<int>(),

thrust::plus<double>()

);

}The d_center_idx give all the coordinates of a vector the same label so that they are be grouped together in the reduction step.

Map points to centers step

To find the accumulate sum of points with the same label, for each point with a different centroid label, we give each coordinate of the vector a different, so that we have $\text{number of clusters} \times \text{dimension}$ labels. Suppose point $a_1,\; a_2$ are assigned to centroid 1 and 2 respectively, then we label each coordinate as follows:

\[\mathbf{a}_1 = \begin{pmatrix} a_{11} \\ a_{12} \\ \vdots \\ a_{1d} \end{pmatrix} \Rightarrow \begin{pmatrix} \text{label 1}\\ \text{label 2}\\ \vdots \\ \text{label d}\\ \end{pmatrix} ,\hspace{5pt} \mathbf{a}_2 = \begin{pmatrix} a_{21} \\ a_{22} \\ \vdots \\ a_{2d} \end{pmatrix} \Rightarrow \begin{pmatrix} \text{label d+1}\\ \text{label d+2}\\ \vdots \\ \text{label 2d}\\ \end{pmatrix} ,\hspace{5pt}\cdots\]With this, we then use thrust::stable_sort_by_key to sort the input dataset array of size (number of points*dimension) by the above labels, then use the labels as key and use thrust::reduce_by_key to accumulate points with the same labels.

Calculate number of points in each centroid

After each point is assigned to its nearest centeroid, the number of points in each centroid can be found by

thrust::reduce_by_key(

d_labels.begin(), d_labels.end(),

thrust::constant_iterator<int>(1),

thrust::make_discard_iterator(),

d_ClusterCounts.begin()

);Comparison between different implementations

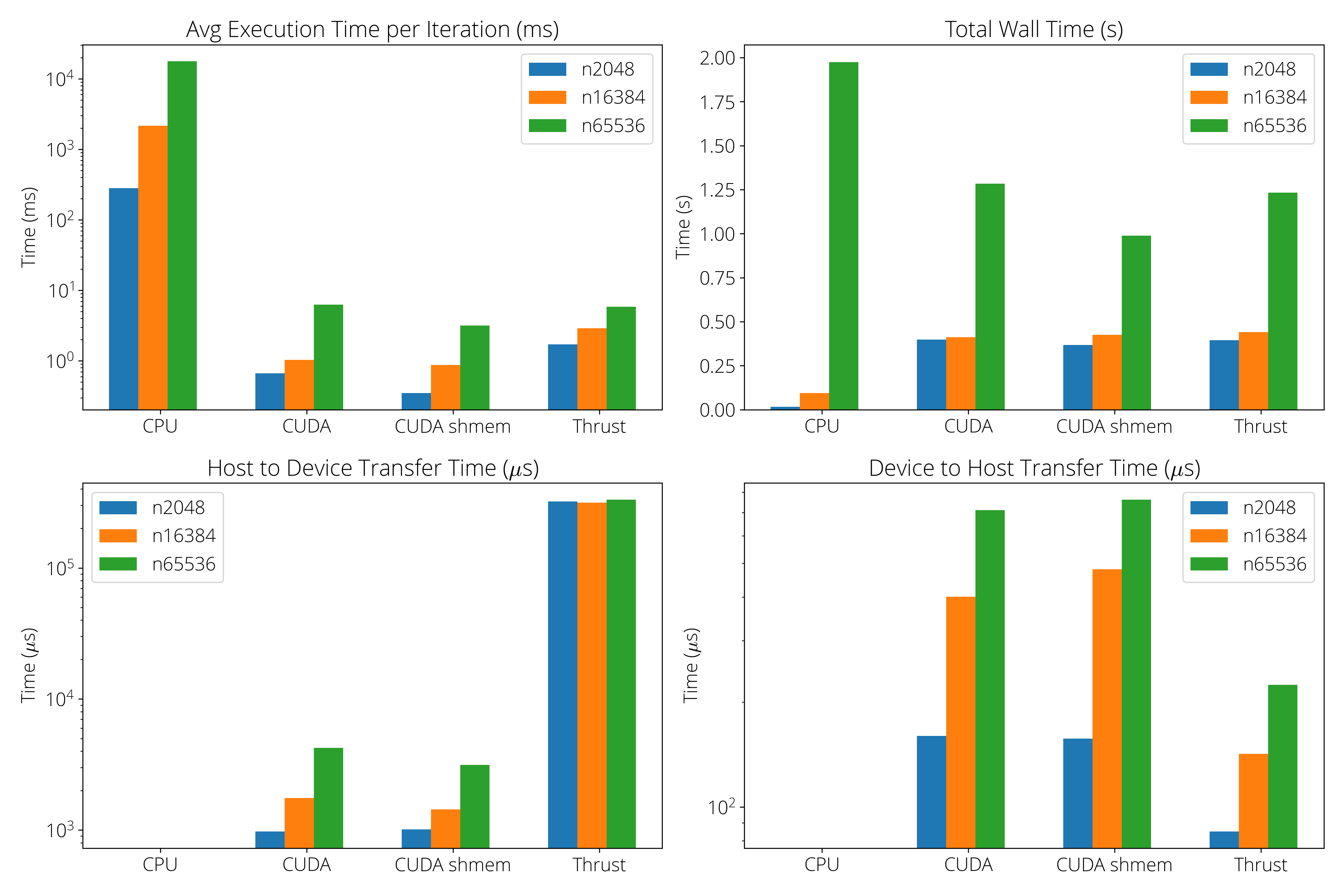

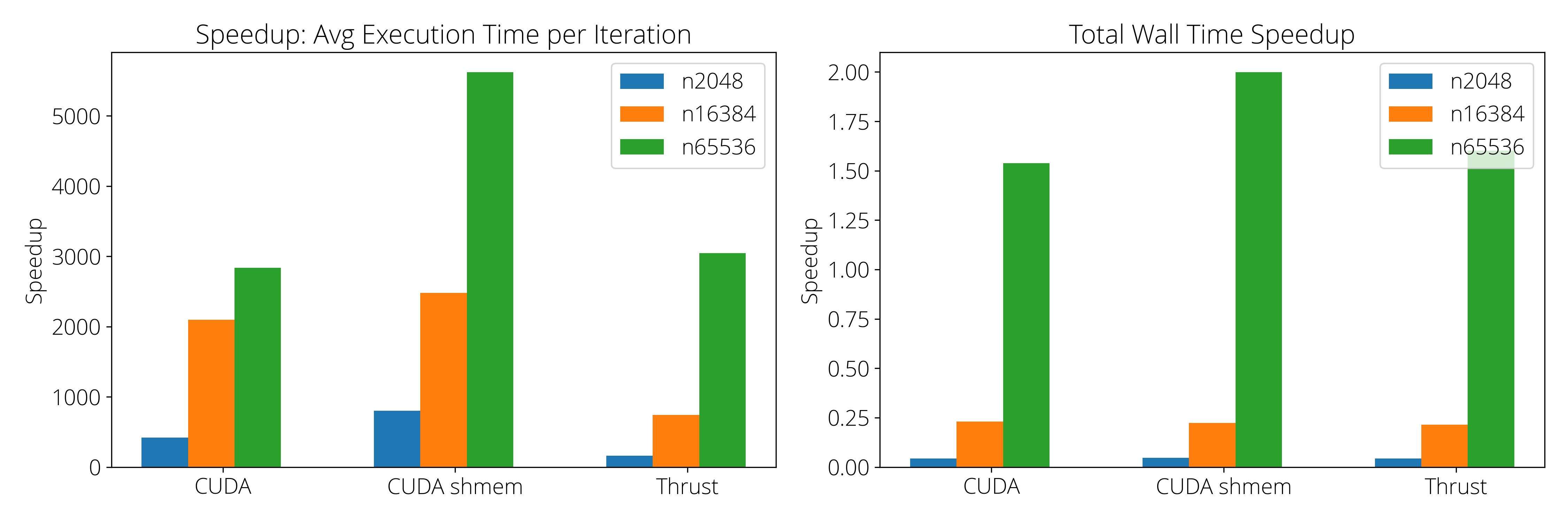

We ran the kmeans algorithm on our CPU (serial), basic CUDA, CUDA shared memory and Thrust implementations. For each implementation, we timed and profiled the execution on three different input sets: (1) \texttt{random-n2048-d16-c16.txt} has 2048 points and each point is of dimension 16. (2) \texttt{random-n16384-d24-c16.txt} has 16384 points and each point is of dimension 24. (3) \texttt{random-n65536-d32-c16.txt} has 65536 points and each point is of dimension 32.

The experiments were conducted on a machine with an AMD Ryzen 5600G CPU (6 cores/12 threads), running Ubuntu 22.04. The GPU used was an Nvidia GTX 1080Ti with 11 GB memory, featuring 3584 CUDA cores, 28 streaming multiprocessors (SMs), and an L1 cache size of 48 KB per SM